‘We all have to do this work’: Paul Farmer’s greatest legacy is the people he left behind

A year after Dr. Paul Farmer’s death , daily life, for the people who knew him, is much the same as it always was. His colleagues are still caring for patients, still thinking about how to best support people, still advancing the ideas of global health equity.

And yet, everything is different. His loss has been profound.

Farmer’s colleagues and friends are doing their best to hold onto the lessons and experiences he invited them to share, all while grappling with the question: How do you move forward after someone so important dies?

Cog talked to 10 people who inhabited Farmer’s orbit. To mark the first anniversary of his death, we asked what they missed, what they remembered and what they hope to carry forward.

"I really miss just knowing that Paul is out there," Dr. Louise Ivers told us. "Just knowing that Paul is audaciously and boldly challenging the status quo and paving a way for us to do our work." It was a common sentiment.

To a person, the people Cog interviewed said that Paul was human, and that his humanity — his imperfections — were essential to recall as the work continues. There was only ever going to be one Paul Farmer: The movement for global health equity has always been larger than a single person.

They talked about his unflinching ability to lean into uncertainty — and his comfort in countering other people’s certainty, especially when it came to making decisions in communities burdened by the structural violence of poverty and racism. You don't get to despair for the poor , he used to say. You don't get to throw in the towel for somebody else.

They explained his ability to create an authentic and joyful familiarity with nearly everyone who knew him. Farmer was the center of gravity to thousands, and everyone felt their relationship with Paul was special; he was the master of inside jokes and nicknames, a prolific texter and WhatsApp user.

They talked about his commitment to caring for the destitute sick while simultaneously pushing to“rectify and remedy” the structures that impoverished them. That he encouraged his colleagues to be interested in the long-term work of systems change — the results of which would be realized beyond the bounds of his own life, beyond the life spans of many involved — is one of the most rewarding and enduring parts of the work.

And they recalled his car-ride sing-alongs to Nina Simone, his irreverence and sense of humor even in the most dispiriting of circumstances, his belief that happiness doesn’t mean a life without sorrow and loss.

Here are 10 of Dr. Paul Farmer’s colleagues and friends, in their own words.

-- Cloe Axelson

*With thanks to the following people for so generously sharing their time and reflections: Ophelia Dahl, Ishaan Desai, Paul English, Louise Ivers, Antoinette “Toni” Hays, Ingrid T. Katz, Wilfredo Matias, Daniel Palazuelos, Brian Remillard and Monika Kalra Varma.

Paul could always imagine something where there's nothing. It was a great gift to envision a far more inclusive future, and he always held himself and us to a high bar. That quality was a big part of how we built a beautiful university of global health equity in the hills of northern Rwanda. We must have equity in the name , he told me.

In recent years, I asked Paul how he'd most like to focus his time, and he told me simply: reading and writing and teaching. And by teaching, he meant spending time with students and colleagues, teasing out the best in them, investing in people to ensure this work lives on.

I think Paul knew he wouldn't live a long life. He knew he wouldn't see all the results of his work. None of us will. But he was full of beans about the future. And I see him and his spirit embodied in the work through so many colleagues and friends over decades and across continents. I can't think of a better legacy.

-– Ophelia Dahl , c o-founder and chair of the board, Partners In Health

Happiness for Paul didn't mean freedom from sorrow or loss. It was rather the act of engaging in caring for others in close proximity to them and direct service to those who suffer most. That's what he meant by happiness.

And I think that's just a very important lesson for all of us, not only in medicine, but as human beings. An understanding of suffering is important, but it's made more pragmatic and more meaningful when we link that understanding to practical efforts to lessen the suffering. And that's what Paul did, I think, better than anyone, and what he taught many of us.

-– Ishaan Desai , s tudent, Harvard Medical School, Dr. Farmer’s research assistant (2015-2022)

Paul’s humanitarian work is profound, but he was also a deep thinker, and his scholarship, writing and concepts are really important. I would like people to read his work and think about it in an intellectual way, as well as thinking of him as a humanitarian. I want folks to deeply engage with that part of him, at the same time they remember him as a person that they would aspire to be.

-– Louise Ivers, MB, BCh, MD, MPH, DTM&H, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Global Health, professor of medicine, global health and social medicine, Harvard Medical School

Over the last year, there’s been a lot of grieving. There's been a lot of trying to figure out how we move on. There’ve been so many moments when I’ve wanted to talk to Paul — to get some clarity. But a lot of things are exactly the same. We’re taking care of patients. We’re thinking about how to support people that need help. We're thinking about how to advocate for global health equity. I'm sure many others are feeling this energy, when we realize that Paul basically left us a blueprint of how to do this work. And he created a family and large community that really spans the globe.

-–Wilfredo R. Matias MD MPH Infectious diseases fellow, Mass General Brigham; Research fellow in medicine, Harvard Medical School

I've come to miss how his incredibly audacious moral spirit invigorated our ambitions. I think that he had this incredible ability to always call out the right thing to do — even when it wasn't expedient to do or even polite to say. He put the primacy of people above everything else.

-– Daniel Palazuelos, MD MPH Director of community health systems, PIH, Assistant professor Harvard Medical School, Assistant director of the Hiatt residency in global health equity at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Paul had exceptional talents, but the thing that you sensed around him, was his commitment. He committed in a way that few people can. I’m not a big skier, but I’d say it's kind of like looking down a double black diamond and dropping in. Paul never hesitated, he just dropped in. I think that’s also a frightening thing for people, because you realize that in your life you could do partly what Paul did — if you're willing to commit as much as he did. That's really the difference between a lot of people and Paul: He would just do it.

-- Dr. Brian Remillard, chief of nephrology, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, associate professor of medicine, Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine

I think Paul was really human, like we’re all human. When someone who has done so much for the world leaves us, we wonder how we could fill that void. But Paul was very real about who he was. He was funny and he'd get irritated and he would let us be those things. It means that there is not this perfect person out there that has to do this work; we all have to do this work.

-- Monika Kalra Varma, CEO Boardsource

Paul would always say — and it's now my mantra — don't worry about the money. Just do it because it's the right thing to do, and we'll figure out how to pay for it later. And that is exactly how we do it .

-- Antoinette Hays, RN, PhD, p resident of Regis College

There’s no other Paul. But there are many, many Paul proteges, Paul disciples, and people who hold him as their “North Star.” And I think what's beautiful about this community is we all believe in this work. We're all doing it in these different ways.

Paul was the seed that planted the sapling that grew into the tree that now bears an enormous amount of fruit. And we're all those beautiful different fruits that are all trying to give to the world to make it a better place. He put the good soil down. And just like his gardening, this was what happens when you nurture people who care about this work.

-- Ingrid T. Katz, MD, MHS , associate faculty director at the Harvard Global Health Institute, associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and associate physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital

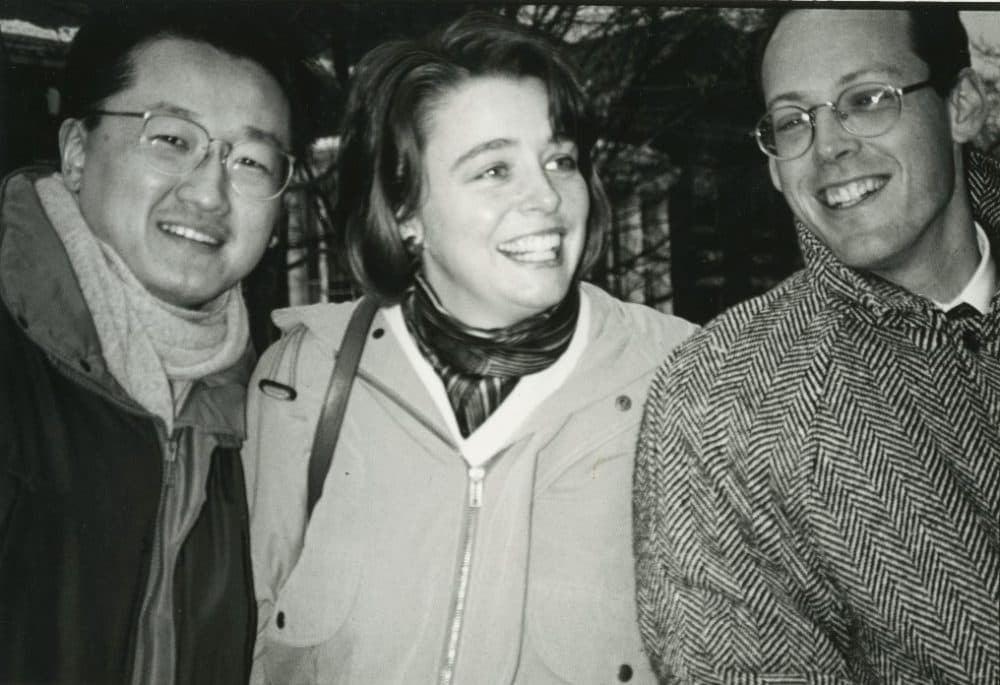

I think Paul knew he wouldn't live a long life. He knew he wouldn't see all the results of his work. None of us will. But he was full of beans about the future.

Ophelia Dahl

I thought that I would have memories of Paul at big events, standing in front of people, the adulation. But instead, I'm always returning to the most private and intimate moments. To dinners that we had, where we were laughing; the time that we were at a restaurant and kept stealing my tequila. He was the type of person that was not afraid to allow humor to break the sometimes sheer sorrow of our work and the challenges that we face.

-– Daniel Palazuelos, MD MPH Director of community health systems, PIH, Assistant professor Harvard Medical School, Assistant director of the Hiatt residency in global health equity at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Paul, like all humans, was a complicated person, and he was relentless in his desire to achieve the mission of equity and justice. And sometimes that made it hard. It made it hard because it could feel impossible to be like Paul. It could feel impossible to fulfill the mission that he wanted to fulfill. And I think it's important to realize that he was human and he had human failings like we all do. It’s important to know that, because to do the work — to advance the work -- you can't wait for somebody who you think is just this really aspirational, saintly being to do the work on your behalf. You have to do the work. And the work is hard.

Paul was successful in his work, but also never felt like it was finished. And grappling with those tensions of how as humans we can change the world we live in and inspire others to do it while we deal with our human realities is really important.

-- Louise Ivers, MB, BCh, MD, MPH, DTM&H, director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, director of the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Global Health, professor of medicine, global health and social medicine, Harvard Medical School

Paul taught me how to think big. And how to not have limits. He also taught me to be focused not on the nonprofit, but on the person who's suffering. It’s thinking about the systems that hurt people, and also how we can help each individual.

-– Paul English, entrepreneur and activist

The work that we do, not just in global health or health care, but any work that is focused on advancing social justice and supporting the underserved, it's really hard work. You're losing most of the time. And when Paul was around, even though things were challenging and things weren't going the way you wanted them to, you always knew that Paul was out there, and that he was on your team, and that he was doing the same thing and showing that it could be done.

-- Wilfredo R. Matias MD MPH Infectious diseases fellow, Mass General Brigham; Research fellow in medicine, Harvard Medical School

I think we're more determined than ever to fulfill this legacy. We were there with him, and we would wait for him to push us along and keep inspiring us. Now we have to do it for ourselves, and we're more determined than ever to do so.

-- Antoinette Hays, RN, PhD, p resident of Regis College

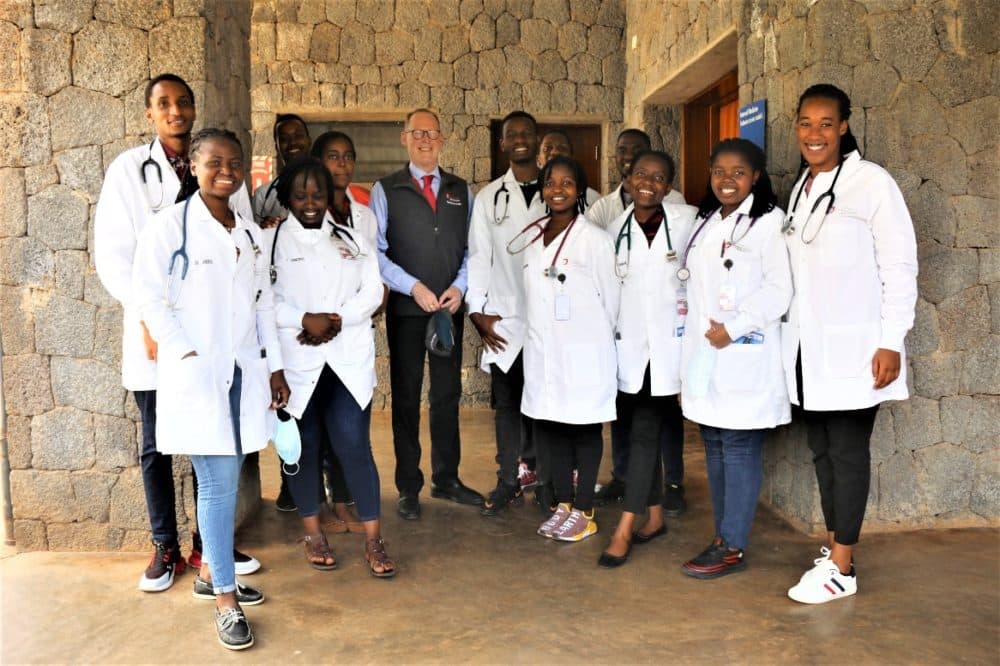

Happiness for Paul didn't mean freedom from sorrow or loss.

Ishaan Desai

During my first weeks in medical school, I met so many phenomenal classmates who were dedicated to equity and justice and health care. And it just pained me more than anything else that we would be the first class of medical students in decades to not have Paul as a teacher in the clinic or the classroom.

While I wish I could claim that Paul's memory has driven me to do big things and make a big impact over the past year, that's hardly the case. I think instead, it manifested in my life, in more subtle, if still meaningful ways. I feel Paul's presence in very mundane moments when, for example, I spend an evening visiting a lonely patient from East Africa who had been hospitalized for terrible pain associated with their sickle cell disease. Or last week, when I soaked the feet of a man whose health had been ravaged by addiction and incarceration and homelessness.

One coincidence in October, on what would have been Paul's 63rd birthday, I had a chance to meet and comfort my first patient with AIDS in Boston. His CD4 cell count, which is a marker of immune function in patients with HIV, had fallen dangerously low. And it was this very humbling reminder of the barriers still faced by patients in our own country.

-– Ishaan Desai , s tudent, Harvard Medical School, Dr. Farmer’s research assistant (2015-2022)

I went to Haiti with Paul, back in 2007 or 2008. And it was a tough time. I was kind of frustrated and depressed and feeling like I was failing. And Paul took me to the hospital and made me plant a tree. I've spoken about that, what that means to me metaphorically. I think every day, when things feel really horrible or hard, we can plant a tree and do something beautiful – it will make us feel better that we've done something tangible, but more importantly, that we’re being a part of something bigger. We can plant a tree every day. On the hopeless days, there’s still something that we can do.

-- Monika Kalra Varma, CEO Boardsource

Paul had an ability to be really comfortable with uncertainty at a time when it feels as though people need more evidence than ever to be able to take action. Taking risks, judiciously, on behalf of others, was to him an imperative. The work we’ve all done together is based on needing to have a certain amount of comfort with immense complexity. There are times when you’re doing something on behalf of others, and you don’t know if it will alleviate suffering or not. But I think Paul felt very comfortable countering people’s certainty, and his opposition to it led to really important changes: once risk had been taken, it was easier for lots of people to be on board.

-– Ophelia Dahl , c o-founder and chair of the board, Partners In Health

This piece was produced by Cloe Axelson, with help from David Greene.

This segment aired on February 21, 2023.