Advertisement

Mass. lawmakers to wade into fierce debate over court-mandated mental health care

PlayIt was a spaghetti dinner that made Rachel Cappucci try to force her brother to get mental health care.

Brad Cappucci, who was 29 at the time, had cooked the meal at 3 a.m. and then left the stove on unattended. Luckily, their mother discovered it before any major damage was done.

His lapse was the latest in a series of potentially dangerous, erratic behaviors — a sharp downward spiral that left Brad's family desperately searching for help.

"There really was not a resource other than voluntary therapy or seeing a psychiatrist," Rachel Cappucci said. "He didn't want that. He didn't think anything was going on."

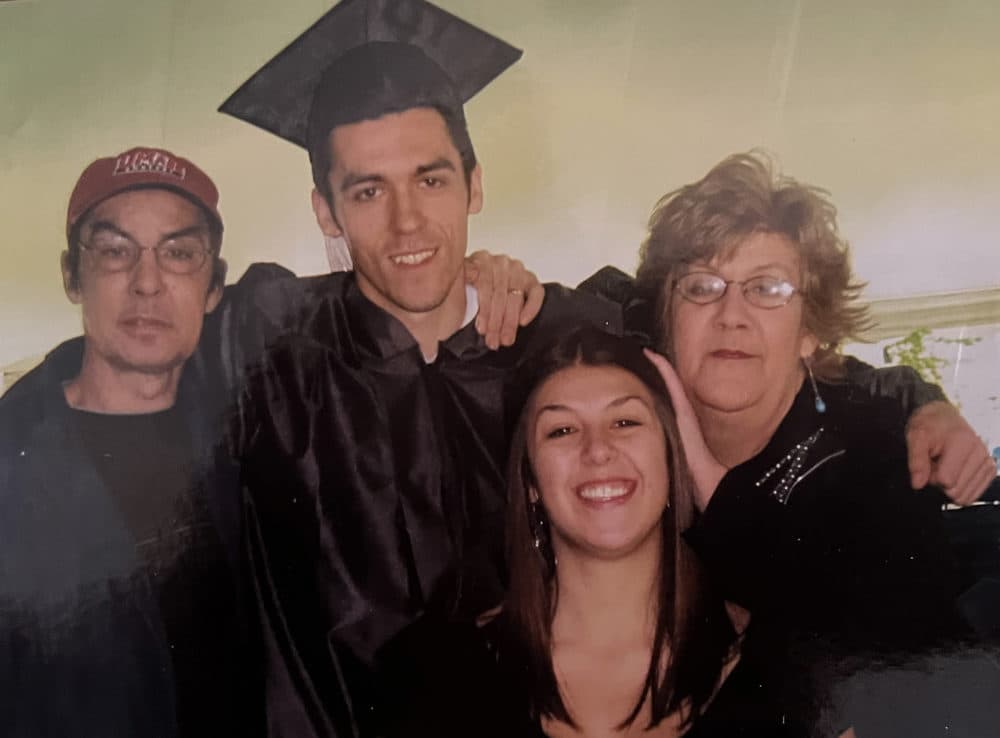

But Cappucci knew something was wrong. She said she'd always looked up to Brad, who was a star athlete in high school and graduated from college with honors. Yet, in just a few years he had become reclusive, irrational and delusional.

In 2017, Brad was living in the basement of their childhood home in Shrewsbury. He often appeared disheveled and was sometimes bruised from hitting himself. After the spaghetti dinner, Cappucci and her mom sought an involuntary psychiatric commitment for Brad.

"At that point, with treatment, I really believed that Brad could come back from this," Cappucci said.

Under a Massachusetts law known as Section 12, a judge can be asked to compel a person to enter a psychiatric facility for an evaluation and possible treatment. But the judge determined that Brad did not meet the legal requirement of posing a harm to himself or others. He was soon released.

Once a patient leaves a mental health facility, there is no mechanism in state law to require the person to continue treatment.

Massachusetts is one of three states that does not allow judges to mandate outpatient mental health care, a process sometimes called "assisted outpatient treatment" or "involuntary outpatient commitment."

Cappucci wonders whether a change in state law could have helped her brother and others like him who struggle with their mental health but refuse treatment.

State Sen. Cindy Friedman, a Middlesex Democrat, has renewed a legislative push to allow court-ordered outpatient mental health care in Massachusetts. Her bill , "An Act to Provide Critical Community Services," is expected to prompt fierce debate at the State House.

Most mental health advocacy groups in Massachusetts are opposed to the proposal. They argue the government should not be involved in overseeing mental health care, and they say the state should focus its limited resources on improving voluntary mental health treatment, rather than forcing it on people who don't want it and adding new court costs.

But supporters, among them many family members who have struggled to get care for loved ones, say court mandates might assist some people who need help. They argue that a new legal tool could prevent some hospitalizations and reduce incarceration for people with mental illness.

Lawmakers are expected to hear emotional testimony from both sides, including families like the Cappuccis and their story of what happened to Brad.

The struggle to get mental health care

Rachel Cappucci said Brad didn't show signs that he was struggling with his mental health until his late 20s. After graduating from college, he was living on his own and working as an economist. It came as a surprise when Brad's employer called their mom, who was Brad's emergency contact, and recommended a psychological evaluation because Brad had been missing work.

"Brad was the portrait of responsibility," Cappucci said. "Finding out he wasn't showing up to his job, you know, that was new."

Brad soon lost his job and moved back in with their mom in Shrewsbury. He was sleeping most of the time, stopped making eye contact and was rarely communicative. Rachel and her mom thought Brad was depressed or perhaps needed a break.

The Cappuccis asked a series of judges to order Brad to get treatment, but without success. Cappucci said Brad became increasingly hostile and continued to deteriorate.

"It got to the point where there was no rational conversation," Cappucci said. "He didn't want anyone looking at him, took clocks off the walls, family photos down, urinated in empty laundry detergent bottles so he didn't have to go upstairs. I would say eventually [he was] in a psychotic state permanently."

In 2019, Brad was formally diagnosed with schizophrenia, a brain disorder characterized by unusual perceptions and losing touch with reality. It can include delusions, hallucinations and the inability to form coherent thoughts. Treatment typically involves medication combined with therapy and skills training.

Although exact estimates are unknown, schizophrenia is believed to affect millions of people around the world. It is often diagnosed in late adolescence or early adulthood.

Cappucci thought the diagnosis might finally result in meaningful treatment for Brad. The family again asked a judge to commit him to a psychiatric facility. At a hearing, Brad again was released because the judge determined that he wasn't likely to harm himself or others.

"It was so troubling to think that there we were — in obvious crisis — and the court just told him to go back home."

Rachel Cappucci

"It felt like without a clear suicide attempt there was nothing they were going to do," Cappucci said. "It was so troubling to think that there we were — in obvious crisis — and the court just told him to go back home."

After the hearing, Brad said he was going west for a job. He communicated with his family sporadically for a time, and then not at all. Cappucci tried not to worry.

But in late December 2021, the Cappuccis heard from police. Authorities had found what were believed to be Brad's remains in a wooded area outside Yellowstone National Park, where he apparently had been living. A coroner's report said Brad died of hypothermia. He was 33 years old.

"I know he didn't want to die," Cappucci said."But there was no place for him. He was homeless, and that's the harsh truth. He was loved, and he needed help. But nobody helped. And I don't believe that there are systems in place to do that for anyone."

Advocates debate involuntary treatment

According to The Treatment Advocacy Center, a national nonprofit group that advocates for involuntary commitment laws, schizophrenia affects more than 62,000 people in Massachusetts. The center estimates that as many as half of those with schizophrenia also have a condition known as anosognosia — where the patient is unaware of the extent of their illness. The center supports the Massachusetts effort to civilly commit some patients to outpatient mental health care.

The proposed Massachusetts legislation would establish several criteria for court-ordered treatment. A patient would have to be an adult with a serious mental illness diagnosis and be deemed "gravely disabled." The measure also would require a recent history of psychiatric hospitalizations, violence or threats of violence. State Sen. Friedman, the bill's sponsor, said it could help disrupt a cycle of poorly treated mental illness resulting in criminal charges, homelessness, incarceration and sometimes tragedy.

Friedman said she has heard from a number of people whose loved ones are in jail after "serious crimes that were committed because of their very serious mental illness — and their families and loved ones' complete lack of ability to get them help before something awful had happened."

This bill is different from prior legislation, she said, because it contains narrow criteria and would affect only a small number of people experiencing severe mental illness. Under the bill, Friedman said, people would not be punished for not complying with treatment.

"We don't want to take away people's rights," Friedman said. "But is it really fair to make them go through this incredible psychological trauma because of their illness? This is about treatment and treatment services, and it puts the state on the hook."

But many mental health and legal groups oppose the idea of forcing people into treatment. The Wildflower Alliance, a group that advocates for peer support and fewer medical interventions for mental health, plans to gather advocates at the State House this spring to urge lawmakers not to support the legislation . The alliance's director, Sera Davidow, said legislators' priority should be improving the existing mental health care system, which she sees as broken and overly focused on psychiatric medications.

“We already have a ton of people getting the treatments that involuntary outpatient commitment would force, and they’re not doing well," Davidow said.

Opponents like Davidow acknowledged that mental health care can be difficult to access, but they said court-mandated treatment can harm people by taking away their agency.

"I understand the pain of a lot of families when a loved one is suffering with mental illness. What we are pushing for is less coercive treatment or non-coercive treatment."

Thomas Brown, Mass. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Collaborative

"I understand the pain of a lot of families when a loved one is suffering with mental illness," said Thomas Brown, president of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Rehabilitation Collaborative, another mental health advocacy group. "What we are pushing for is less coercive treatment or non-coercive treatment. We believe that there are alternatives to forced treatment."

The Disability Law Center, another Massachusetts group that opposes the bill, wrote an analysis that found little evidence that court-mandated treatment is effective. The group also pointed to research indicating that it is disproportionately used for people of color.

"It's coercive and it interferes with personal dignity and human rights," said Rick Glassman, the center's director of advocacy. "It diverts resources from people who really want treatment."

The research on court-mandated outpatient treatment is mixed, and states implement their programs differently. Some studies show no improvement in treatment compliance or hospitalization rates in places where courts can compel treatment.

But other studies link involuntary commitment programs to reduced hospitalization and incarceration. Susan McMahon, associate professor of law at Arizona State University, consulted with a national task force on courts and mental health . She said it's unclear whether the positive outcomes reported by some states are solely because of involuntary treatment orders.

"The question, that a lot of people still have which really hasn't been answered is, is it successful because of the court-ordered component of it? Or is it successful because of the wraparound services that these people have access to that they wouldn't otherwise have," McMahon said.

The Committee for Public Counsel Services, the state's public defender agency, has testified against similar legislation in the past, citing concerns that neither the courts nor the mental health system have the resources to implement an effective program. The group has also said there aren't enough legal protections for patients.

Boston's experiment with court-ordered mental health care

There are some providers who believe a judge's authority can help at least some patients stay in treatment. Boston Medical Center clinician Leila Spencer said she's experienced this. It's sometimes referred to as the "black robe effect."

"I'll make a recommendation to a client until I'm blue in the face, and it's, 'Nope, nope, nope,' " Spencer said. "And then it comes from the bench, and it just holds a lot more weight."

Spencer manages the Boston Outpatient Assisted Treatment — or BOAT — Program, a pilot for people facing criminal charges in Boston Municipal Court. Although participation is voluntary, state Sen. Friedman and others point to the program as an example of how court-mandated outpatient treatment might work across the state.

Participants are chosen based on their mental health history and criminal charges. They receive intensive services including treatment, coaching and housing assistance. Boston Medical Center clinicians monitor their care and make recommendations to the judge. On average, four social service providers work with each participant.

Recent graduate Kamari Hope said the program changed his life. At 39, he had been in psychiatric hospitals several times after suicide attempts. He said treatment never seemed to help his depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Through the program, he found a combination of medications and therapy that work for him.

"In every aspect of my life this has helped me, including the people I never thought would try to help me — a judge, the prosecution," he said.

Hope was required to take psychiatric medications and get counseling. In the past, Hope said he couldn't hold down a job. He didn't take care of himself and would often become irrationally angry.

"I think about the person I was a little over a year ago, and it makes me sad," he said.

Now, Hope works two jobs and is reconnecting with his 7-year-old son.

Because he completed the BOAT Program and complied with treatment, prosecutors dropped the criminal charges against Hope. If he had not complied, his case would have been adjudicated in a regular court session.

Since it began in 2020, the BOAT Program has served 163 people, and 31 have graduated. The pilot is funded through a four-year $4 million federal grant.

Judge Kathleen Coffey, the program's director, acknowledged that the array of services offered is rare, but she said courts have to figure out a way to deal with the increasing number of people with mental illnesses entangled in the criminal legal system.

"As judges, it is our responsibility to help people become productive members of society," Coffey said. "In my mind that's what justice is all about."

Last summer, Rachel Cappucci and her mother traveled to the site in Wyoming where her brother Brad's remains were found. She said she doesn't know if involuntary treatment might have helped, but she believes there should be more support for families like hers who felt they didn't have anywhere to turn. She said she hopes that by telling her story, she can advocate for improvements in mental health treatment — court-ordered or not.

"I don't know if spiritually I needed to go to where Brad was, but I knew I needed to lay down on the ground there," Cappucci said. "It helped to see how beautiful it was."

"There has got to be a solution," she added. "I can't imagine how often this has occurred, and it's just going to keep occurring until there's a major shift in the way we look at folks with mental illness."

This segment aired on March 13, 2023.