Advertisement

Commentary

The mother of the disability rights movement knew this: ‘Disabilities are not problems to be solved’

"Disability only becomes a tragedy when society fails to provide the things we need to lead our lives — job opportunities or barrier-free buildings, for example… It is not a tragedy to me that I'm living in a wheelchair." -- Judy Heumann, 1947-2023

Disability rights activist Judith “Judy” Heumann passed away on March 4, 2023, at age 75. Widely regarded as the mother of the disability rights movement, Ms. Heumann played an instrumental role in developing and implementing multiple groundbreaking pieces of legislation, including the Americans with Disabilities Act, or ADA. I am among many mourning her loss and honoring her accomplishments. As somebody with epilepsy, I am also one of many who stood on Giant Judy’s shoulders when I relied on the ADA.

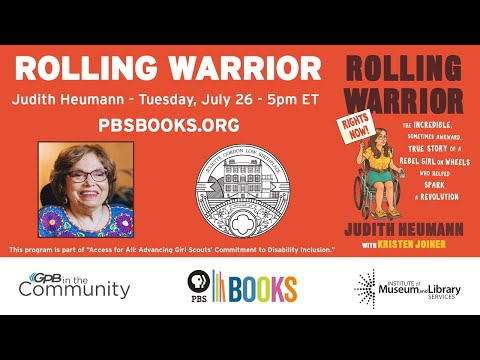

In addition to spearheading actions leading to this critical legislation, Heumann co-authored her memoir, “ Being Heumann ,” and its young adult version, “ Rolling Warrior .” She was featured in the Oscar-nominated documentary film, “ Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution .”

I watched the film three years ago, with my husband and then-13-year-old son, Liam. The documentary features Judy and her peers attending Camp Jened, a New York based camp for people with disabilities. Jened offered typical summertime activities and an atmosphere where campers felt fulfilled as human beings. Crip Camp follows campers’ journeys into adulthood, when, radicalized by the compassion of their camp experience, they became the activists who were integral in the disability rights movement. The film culminates with their participation in 1977’s nearly month-long 504 sit-in , often described as the longest nonviolent occupation of a federal building in American history. The protest led to significant changes to the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, a precursor to the modern-day ADA.

“Is epilepsy considered a disability?” Liam asked when the movie was over. Thanks to double brain surgeries, I’d been seizure-free almost five years by then, but Liam had witnessed dozens of my episodes between ages 0-7. I was diagnosed with epilepsy at age 6 and lived with uncontrollable complex-partial seizures for decades. Prior to 2014, I had approximately seven complex partial seizures monthly. Complex partials are obvious to an observer. I typically lost awareness, smacked my lips and moaned out loud.

The seizures lasted a few minutes and didn’t require medical attention. But prior to 2014, My life was at the mercy of my brain’s misfiring neurons, and although I wasn’t at my best post-seizure, I could resume what I was doing. They were a burdensome nuisance, but like Judy’s feelings about requiring a wheelchair, I didn’t find my seizures tragic. I recognize that witnessing seizures is unsettling for observers. For me, the hardest part was managing others’ reactions to them.

Disabilities are natural forms of human diversity, and people shouldn’t be disparaged because their bodies are differently-abled.

“It is,” I said, in answer to Liam’s question. I relayed the story of my former employer who gave me a poor performance evaluation shortly after I had my first grand mal seizure in 20 years while at work. When I questioned the assessment, my manager told me my colleagues said I looked spacey during meetings, implying that what they perceived as inattention interfered with my capacity to do my job. I thought the seizure, poor evaluation and subsequent disciplinary action were related. I filed a grievance citing the ADA, noting the correlation between my manager’s negative feedback and my increased seizure activity.

“I could threaten to sue my former employer because of the ADA,” I told Liam. “Thanks to the law, I received a year’s salary and benefits.” Liam gave me a high five. “You told them f-you,” he said. I’m not one to encourage my teens to swear, but that was a proud-mama moment for me.

“I did,” I said. “But I couldn’t have done that if it weren’t for the people in this movie who fought for those important changes.”

I remedied that work situation by standing on the shoulders of giants who came before me. And while I’m forever grateful to them for taking actions that led to the ADA’s passage, the frustrating truth is that laws alone won’t change workplace culture because they don’t address society’s fears, intolerance and judgement of those who are differently-abled.

Although I checked “yes” on the disability application question for my current job, I didn’t share my diagnosis with my team for two years. While I may not have seizures, epilepsy still has stigmas. Society, and by extension workplaces, frame health conditions and disabilities as problems to be solved. Consequently, many workplaces categorize disabilities as “afflictions,” resulting in situations like mine.

Disabilities are natural forms of human diversity, and people shouldn’t be disparaged because their bodies are differently-abled. But breaking down these barriers at work requires intentionality. Action steps include calling out disability exclusions when we see them, offering disability fundamentals training for managers and establishing disability-focused employee resource groups. Until workplaces and people in our society take deliberate measures to increase people’s tolerance, empathy and courage, the ADA will have limited impacts.

While society still has significant work to do, this epilepsy warrior is grateful to Judy Heumann and her peers, and to their momentous disability rights advocacy efforts.